Maps of water

Maps of Water (Mappe d’acqua) is an artistic and visual research project developed between Brazil and Italy that investigates the relationship between water, territory, and representation. Through the sustainable technique of mokuhanga woodcut, the project explores how flood events reshape not only the physical geography of places but also their visual and material memory. Maps, pigments, matrices, and surfaces become tools for reflecting on the perception of changed landscapes, the stratification of signs, and the persistent presence of water as a generative, destructive, and symbolic force.

The first field of study focuses on Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, the scene of the catastrophic floods of 2024. The disaster was caused by the combination of an intense El Niño phenomenon, which led to increased rainfall and soil saturation, and structural factors such as intense deforestation, intensive agriculture, and unregulated urban expansion. These concurrent factors were exacerbated by climate change.

Despite the enormous production of cartographies to describe and predict the event, the direct reading of the territory reveals their profound partiality. The impact of floods is dynamic, and the illusion of being able to observe reality from an external and neutral point—the so-called “god’s trick” of Haraway —fails to convey the perceived complexity of the phenomenon.

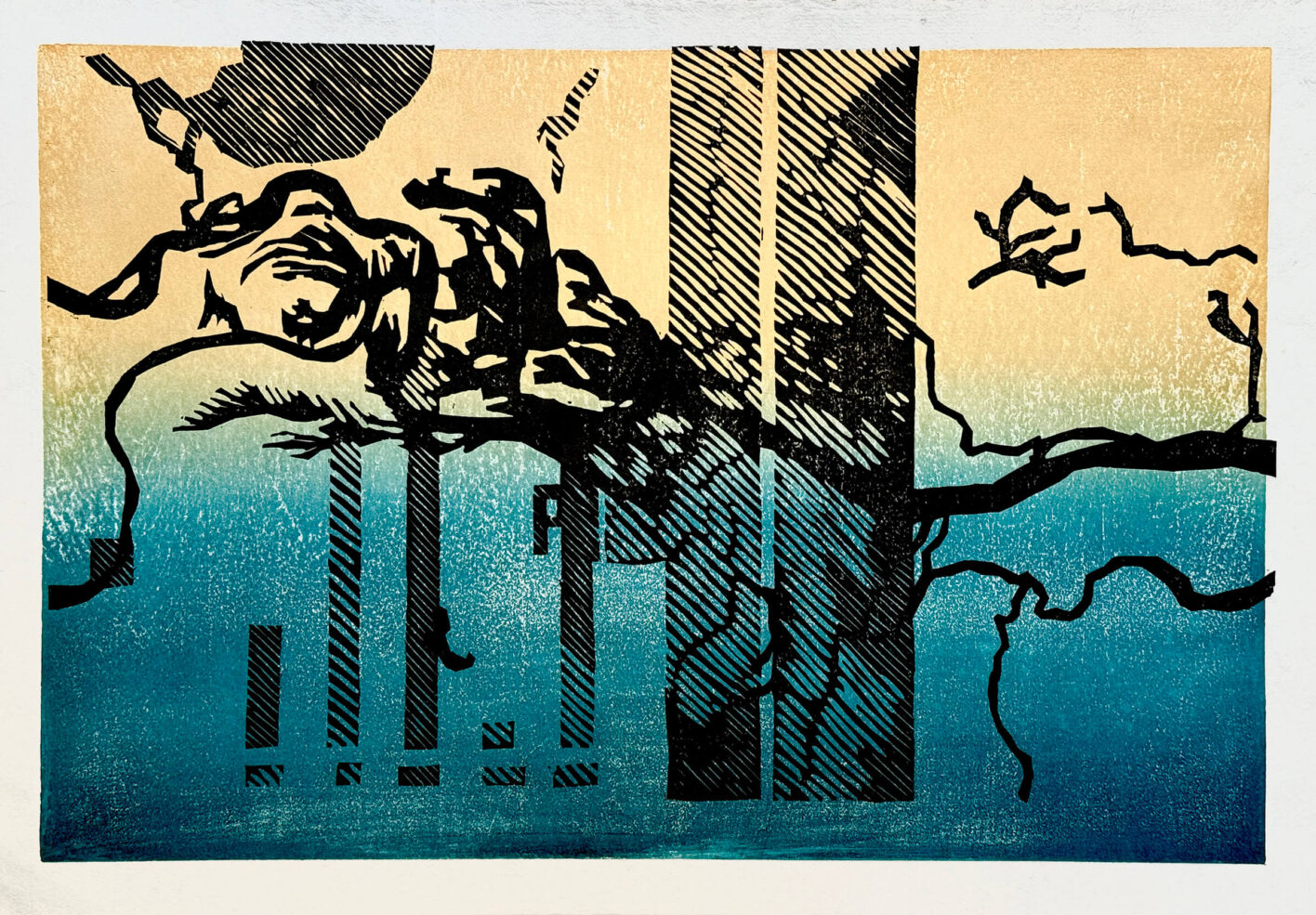

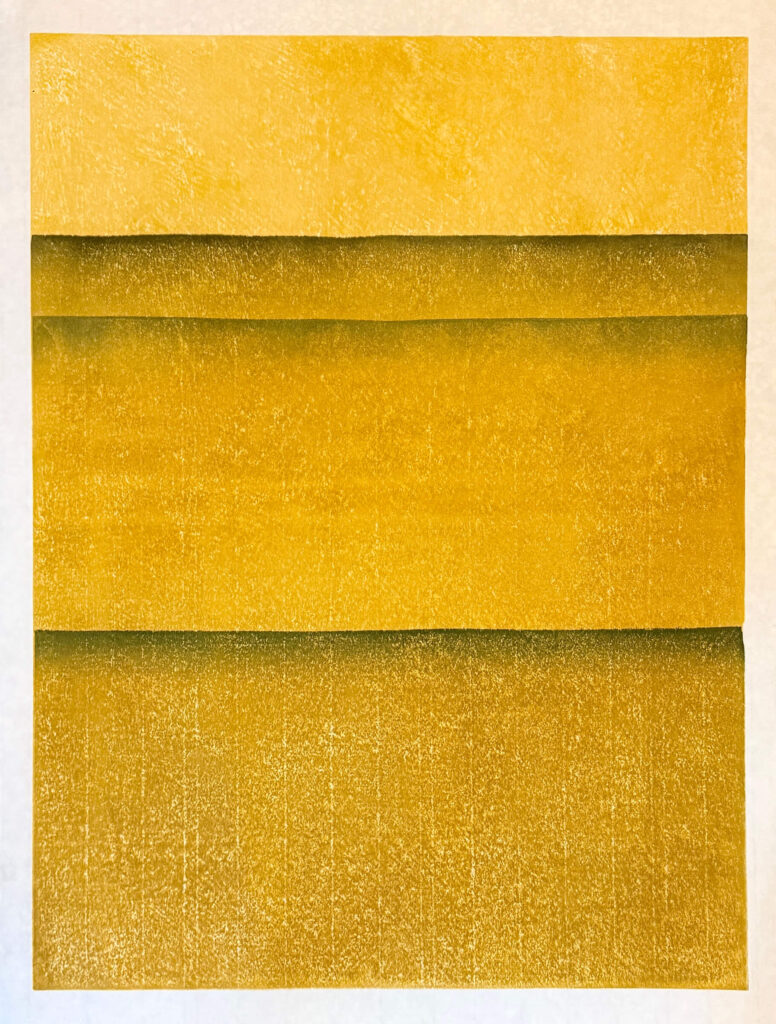

The approach to visualizing the waterways of Rio Grande do Sul focused on the dematerialization of the map. The graphic element of the river is emphasized through the use of halftone, typical of print or screen, functioning as a visual background that underlies the direct experience of the emergency.

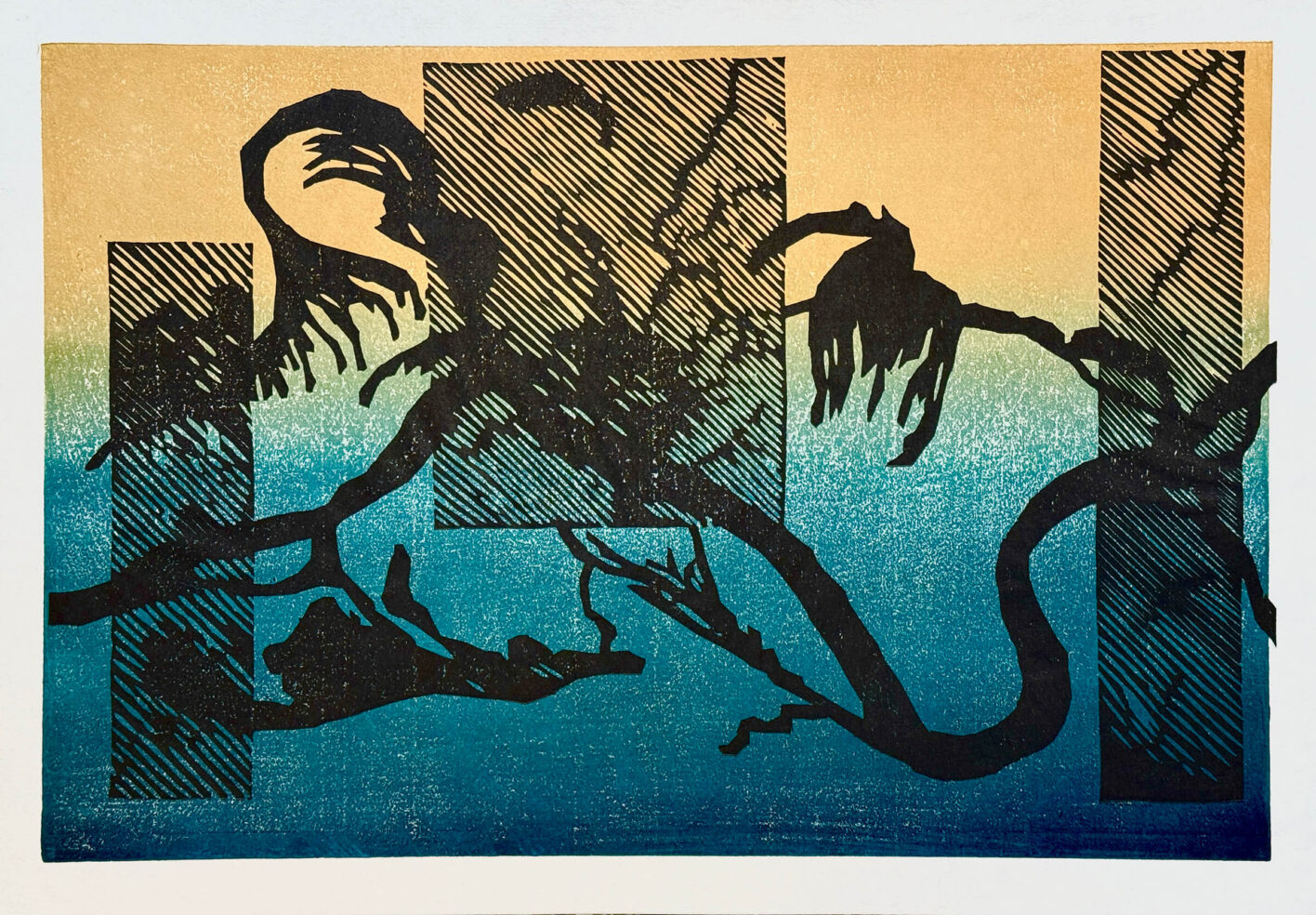

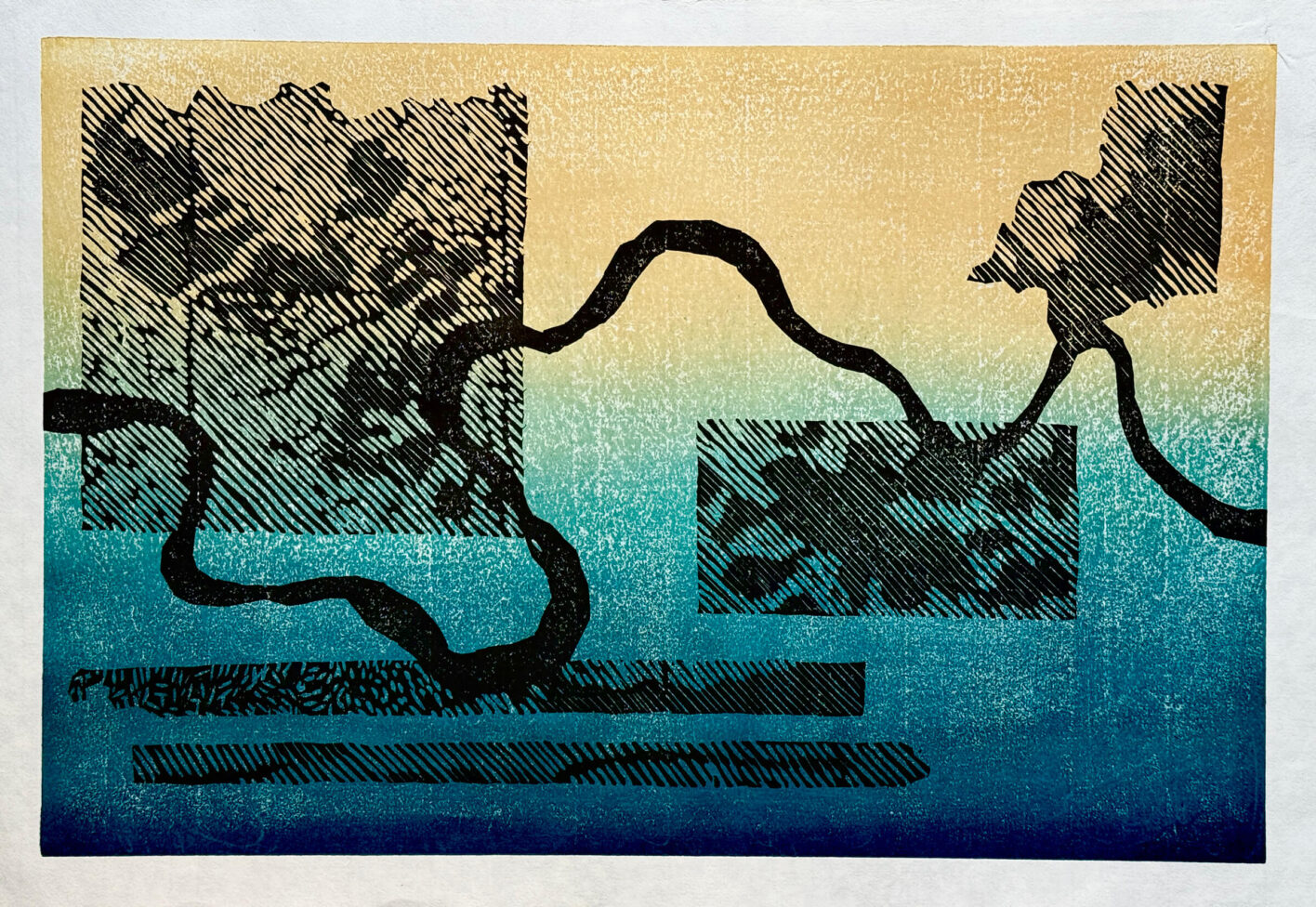

A crucial part of the work involved isolating the shapes of the watercourses, particularly the Rio Jacuí, and then superimposing them onto chromatic gradients that recall the washed-out landscape. This strong decontextualization transforms the river segments into almost abstract crops, questioning the authority and viewpoint of the observer, from where they observe, and with what claim to truth.

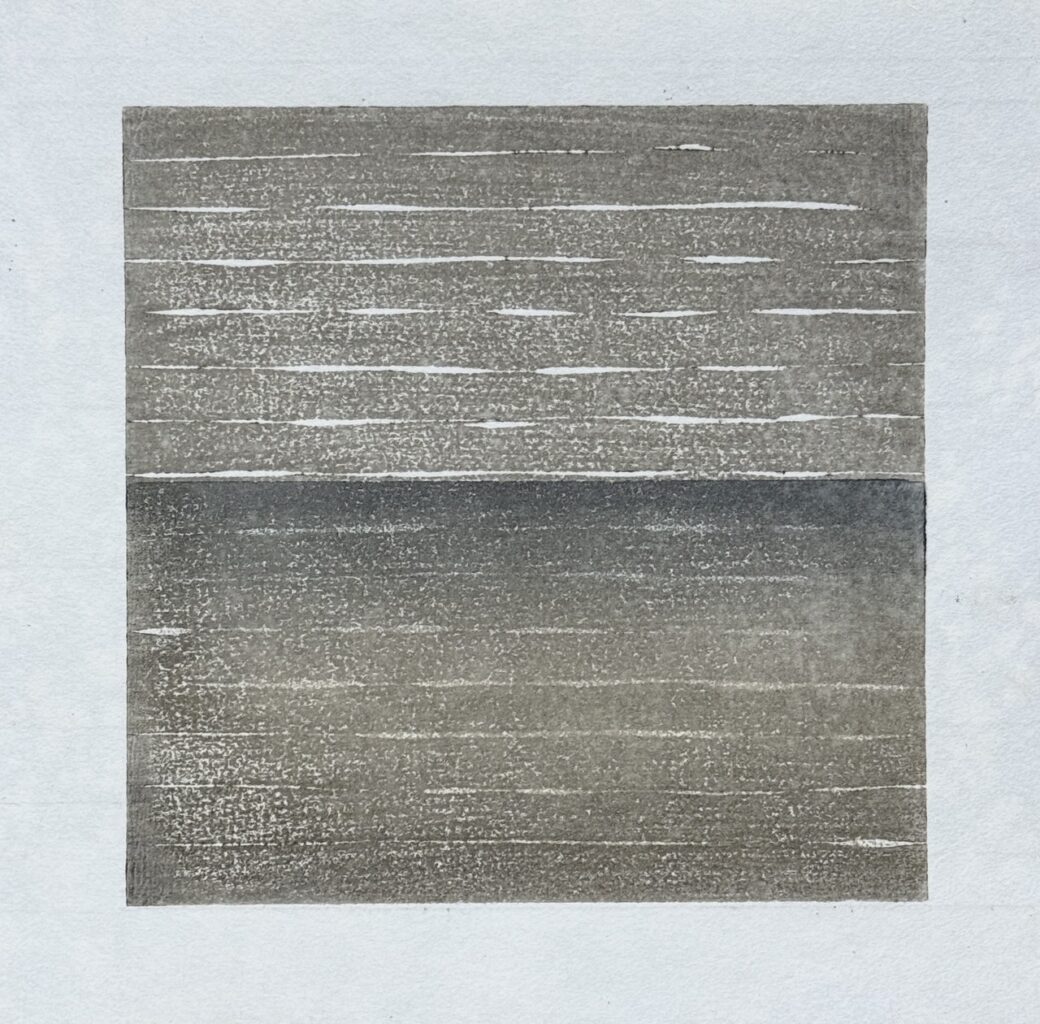

The visit to Porto Alegre reveals the energy and architectural beauty of a city viscerally defined by the presence of water. In the affected neighborhoods, the water lines left by the retreat of the floods remain on facades, walls, and fences. These stratified traces, silent records of rise and retreat, constitute a powerful and involuntary living archive of the event. The entire visual landscape of certain areas is marked by the continuous presence of these superimposed lines, testifying that water does not merely flood, but inscribes its own history onto the surfaces of the built environment.

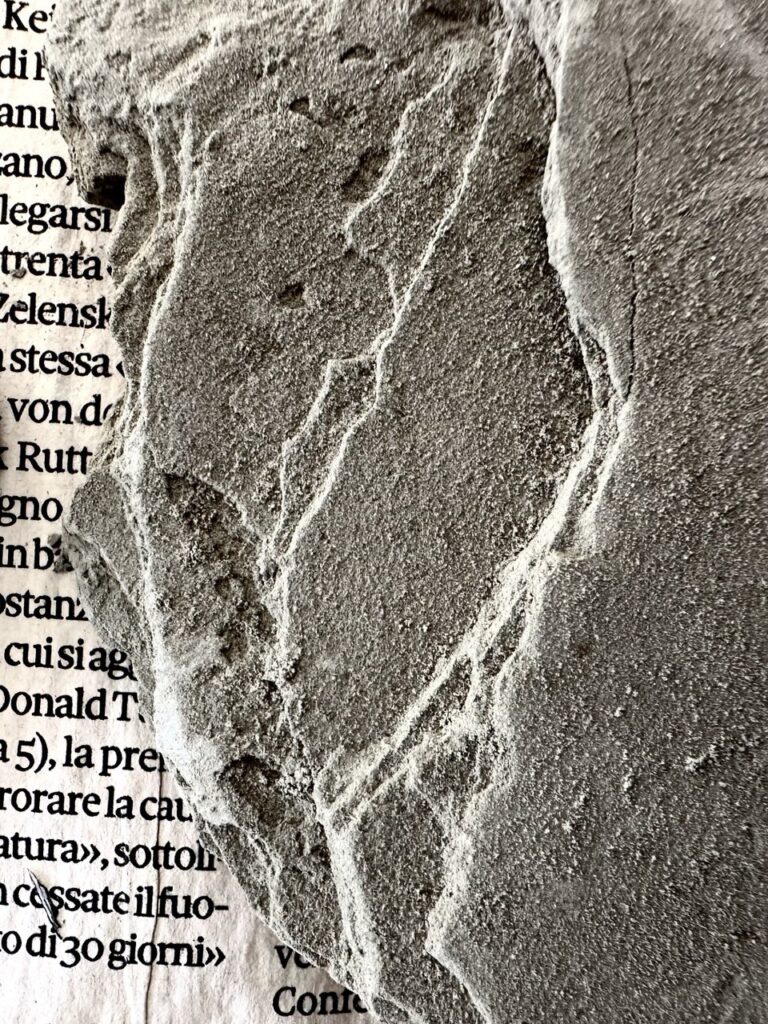

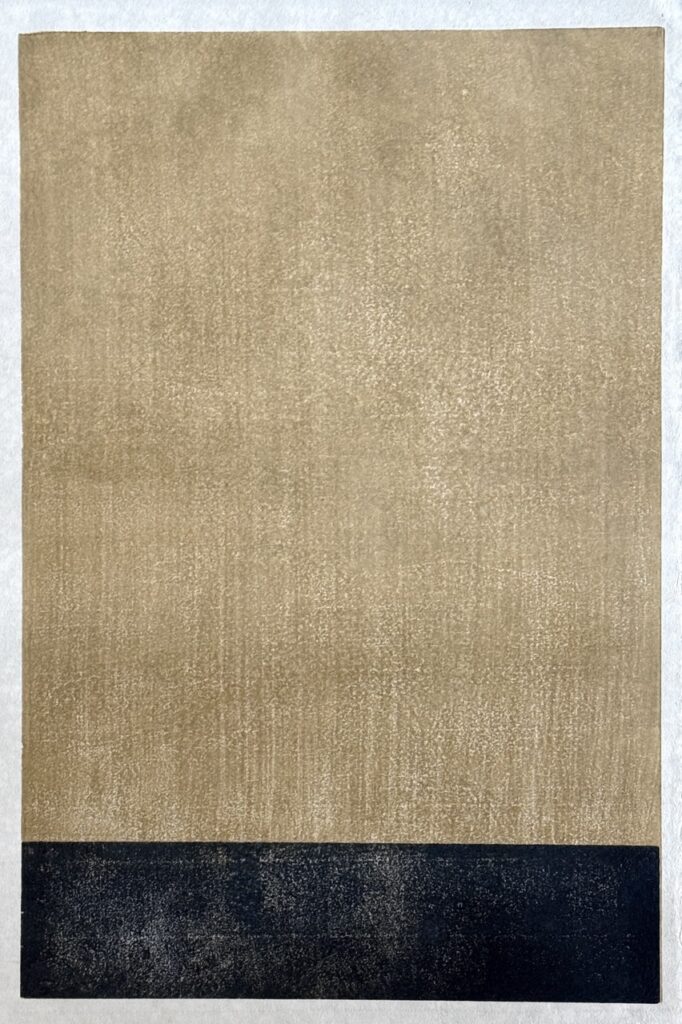

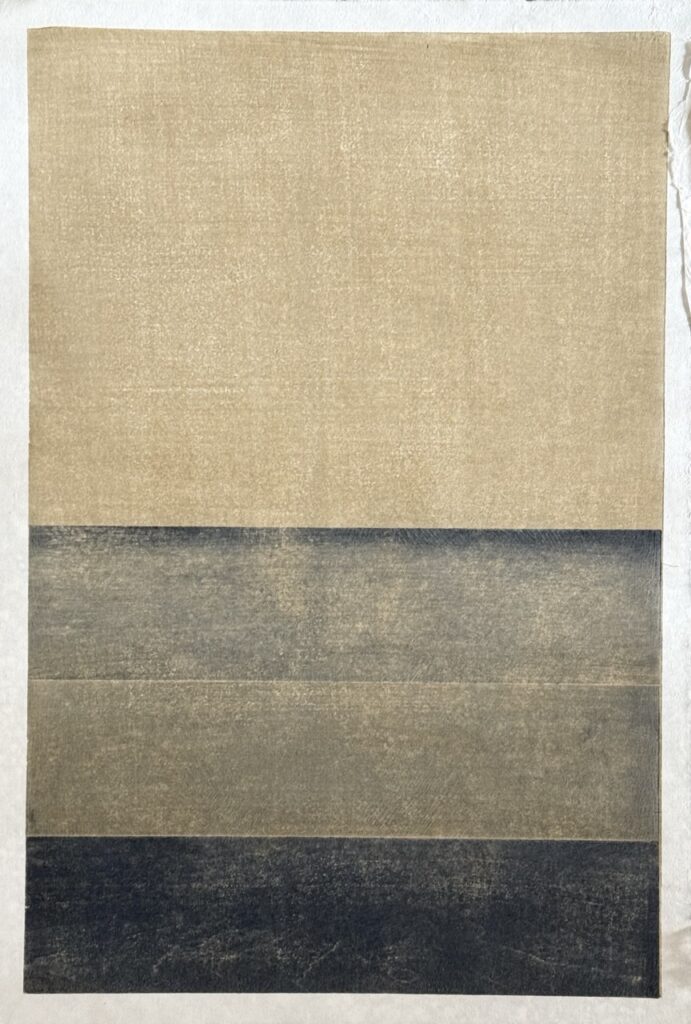

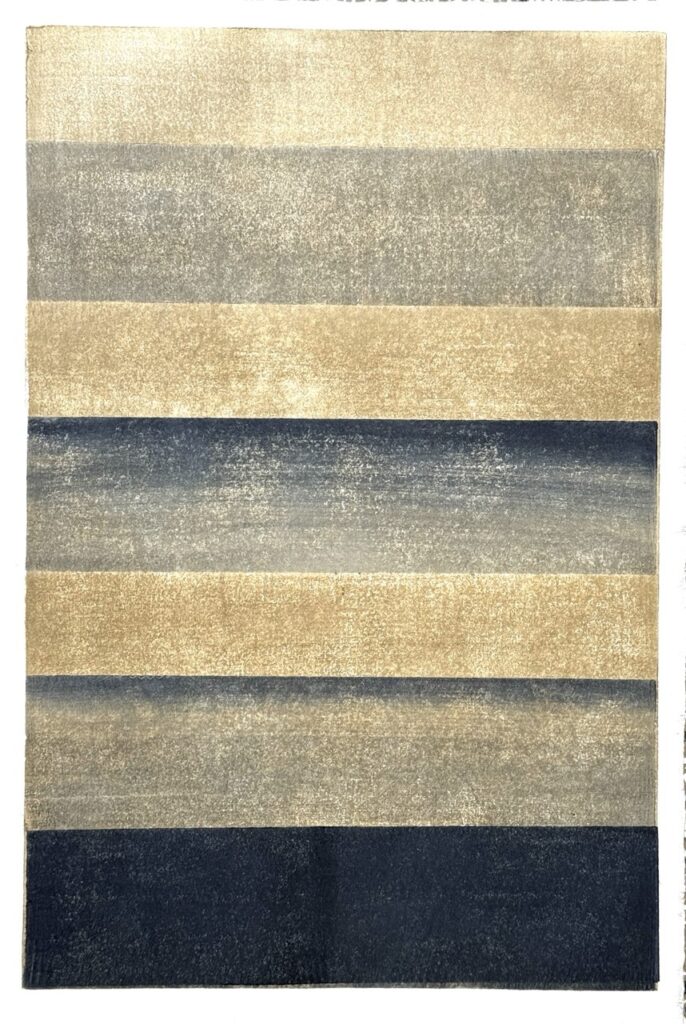

The textures of Porto Alegre’s walls inspired the adoption of the single-block reduction print. The act of carving, which involves the successive and progressive removal of strips from the woodblock, becomes a formal echo of the lowering water levels. The intent is to question the process of spatial representation: no longer just from above, but also from within, through the tactile and visual experience of stratification. Each engraving is configured as a testament, a mark that water not only leaves on the surface but imprints on the sensory memory of the places and the artistic matrix.

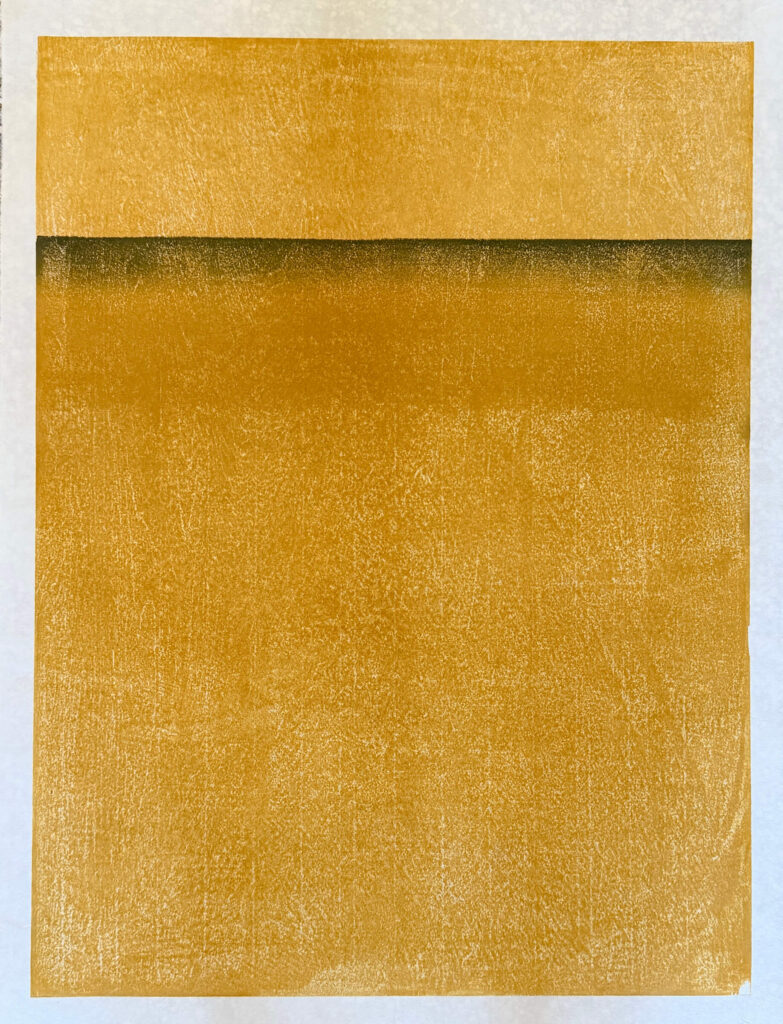

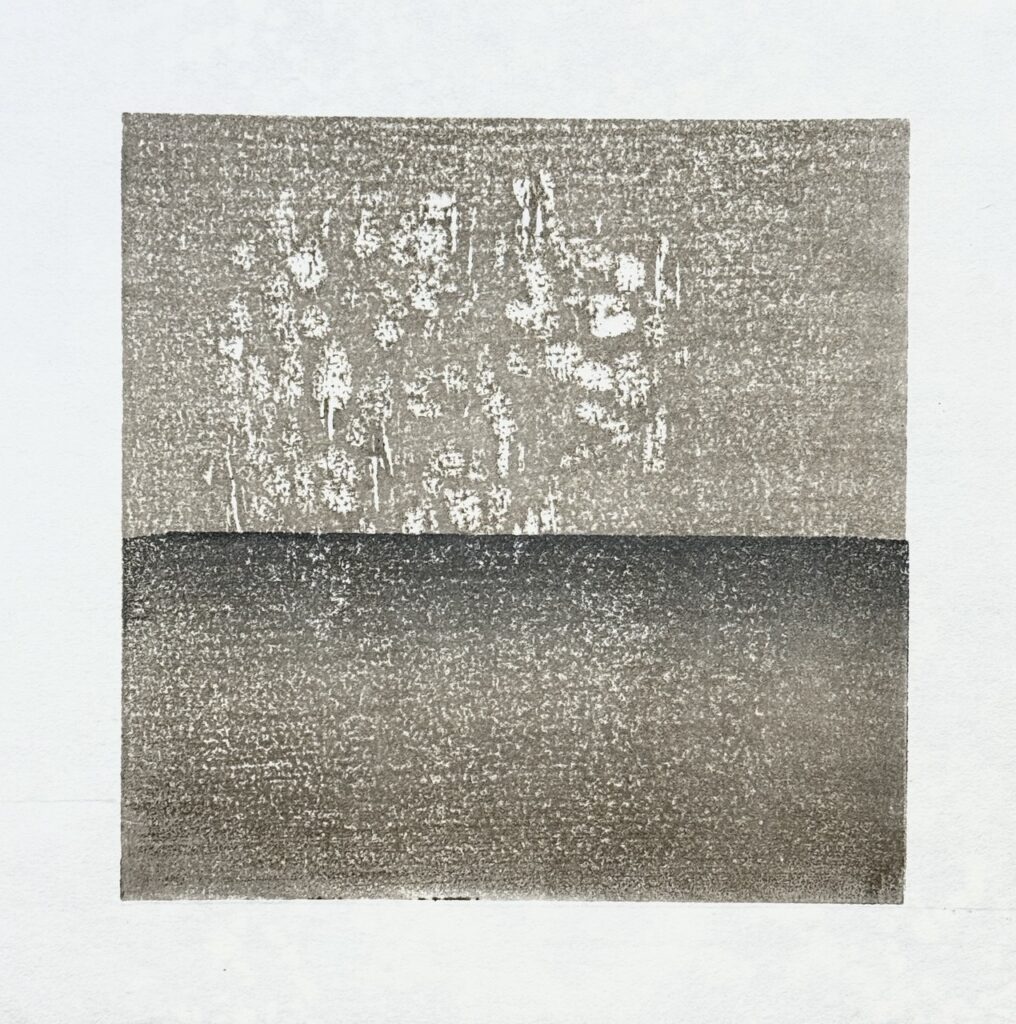

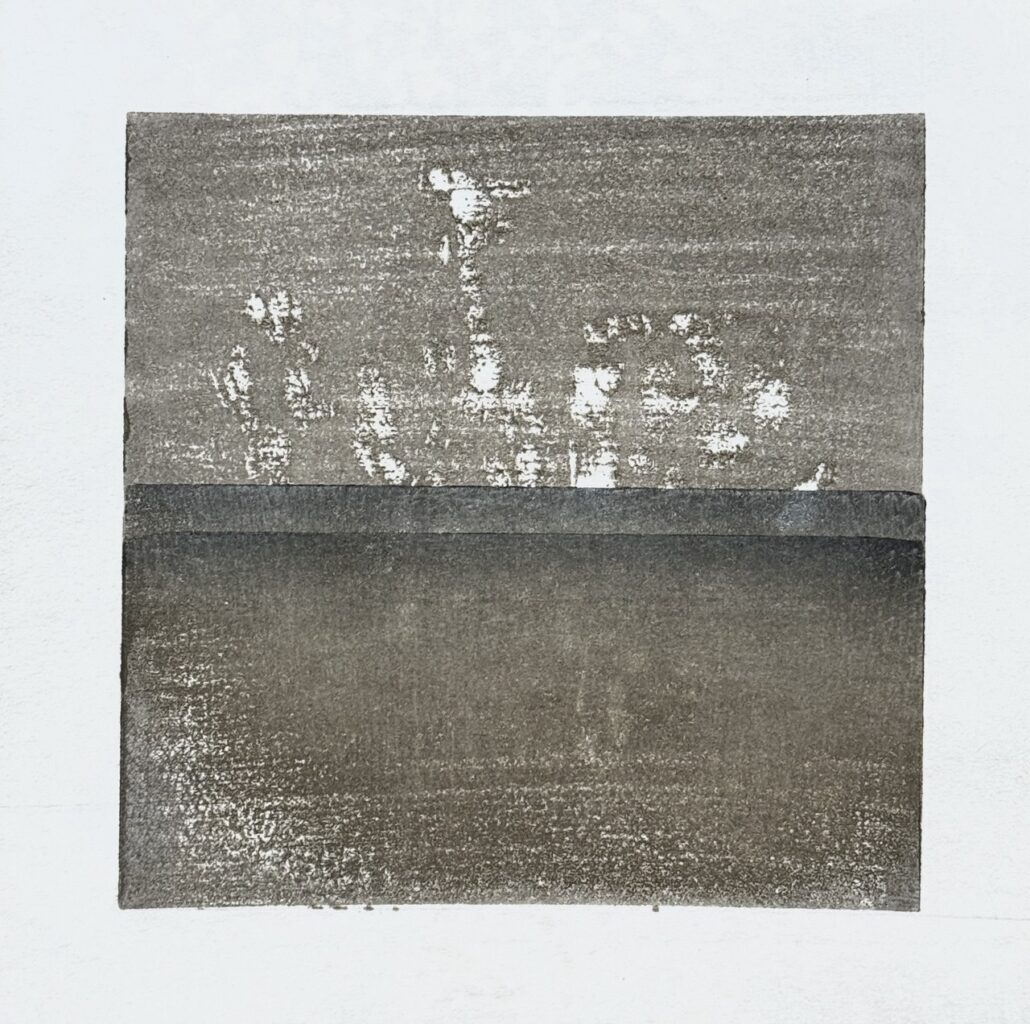

Technically, the project utilizes mokuhanga woodcut, an ancient and refined practice that uses manual tools, natural pigments, water-based inks, and printing methods free from solvents or pollutants. Characteristics like bokashi—the delicate gradation that allows for tonal transitions between colors—and goma-zuri—the natural textures given by manual pressure and the block’s grain—become conceptual tools: not merely aesthetic effects, but ways to make the humidity, sedimentation, the retreat of water, and the stratification of spaces visible. The technique aligns with the intent to render the temporal weight of water palpable.

Returning to Italy, attention shifts to the plains between the Reno, Idice, and Sillaro rivers, near Argenta (Ferrara). These areas, affected by the 2023–2024 floods, are historically shaped by centuries of land reclamation and hydraulic management. The region, partly below sea level and characterized by riverbanks higher than the surrounding land, possesses an intrinsic hydrogeological fragility and a complex history of struggle for water control. The coexistence of fluvial forces and human intervention reveals complex narratives of belonging and dominance.

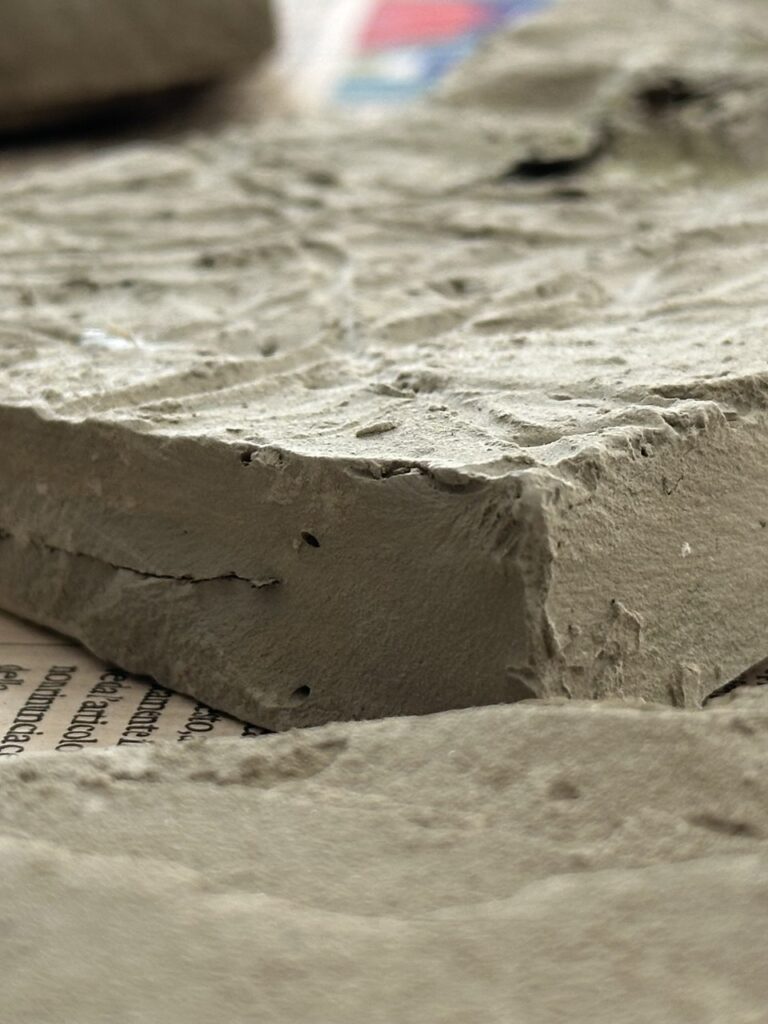

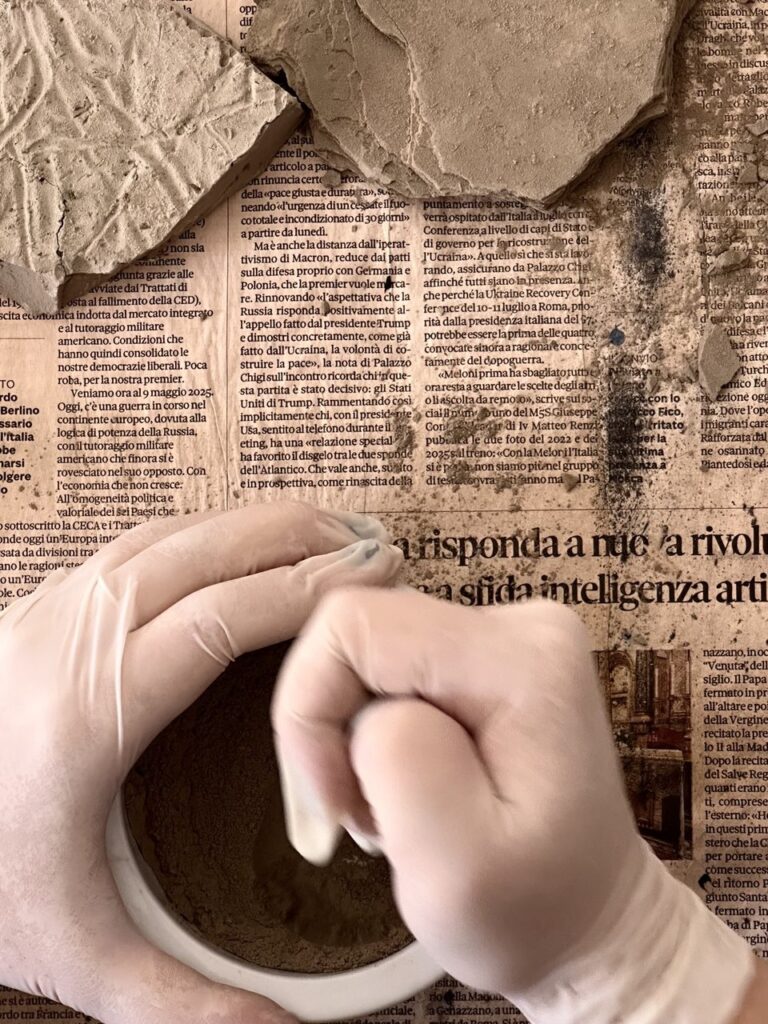

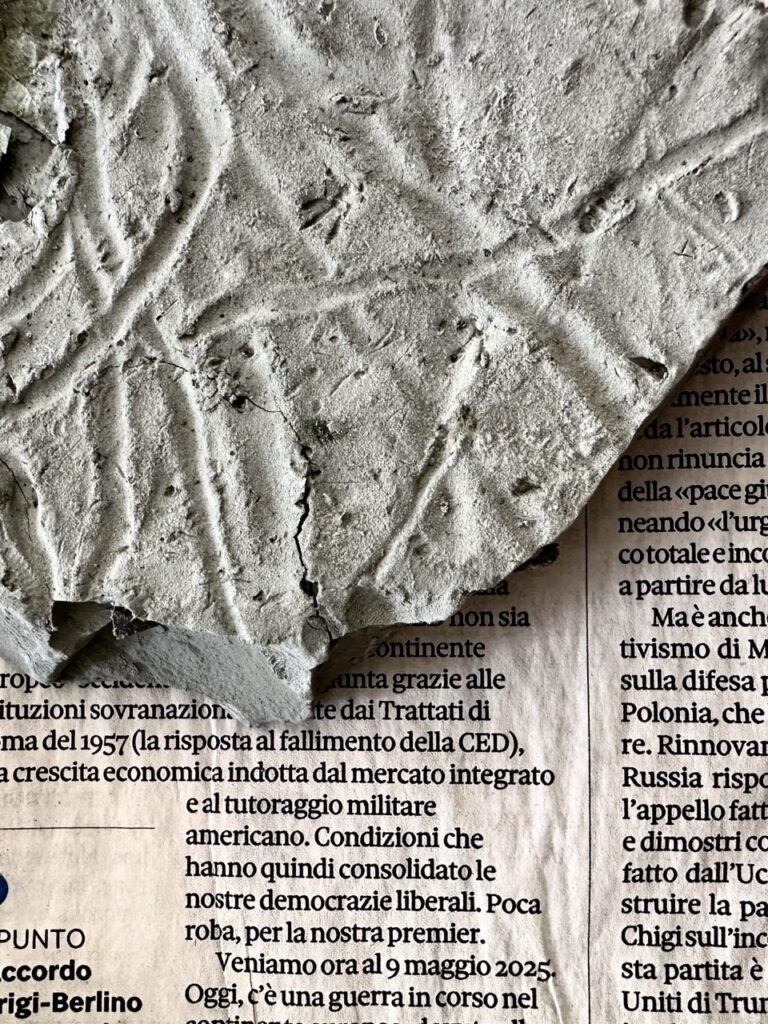

The research extends to the material recovery of the events. In the plains, near the Pieve di San Giorgio, flood deposits still exhibit an almost lunar chromatic veil. Local clay was collected, transforming these sediments into pigment. This process is not merely technical, but symbolic: the residue of the disaster is elevated to an artistic medium, making the work literally composed of the very matter of the event. The clay mixed with the print creates a tactile memory, a way to approach and transform the disaster into a sensible and concrete narrative.

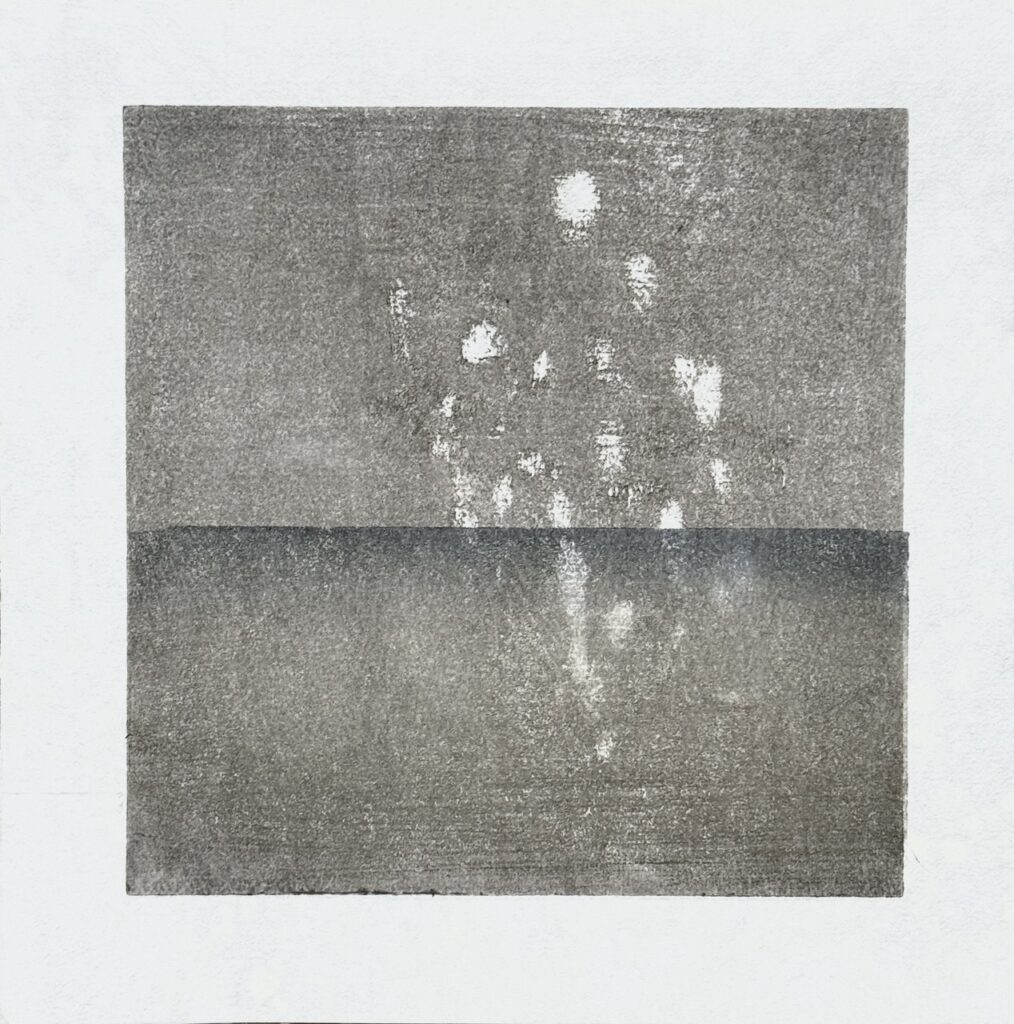

From this clay pigment, a series of small square prints was generated, exploring the concepts of stratification and erosion. Each square is a compact reflection on how water corrodes surfaces, leaves a trace, and inscribes memory into the place. The ground and mixed mud dust serves as a vehicle to represent the rewriting of the landscape’s identity by natural forces. These works, due to their size and process, embody the conceptual density of the event.

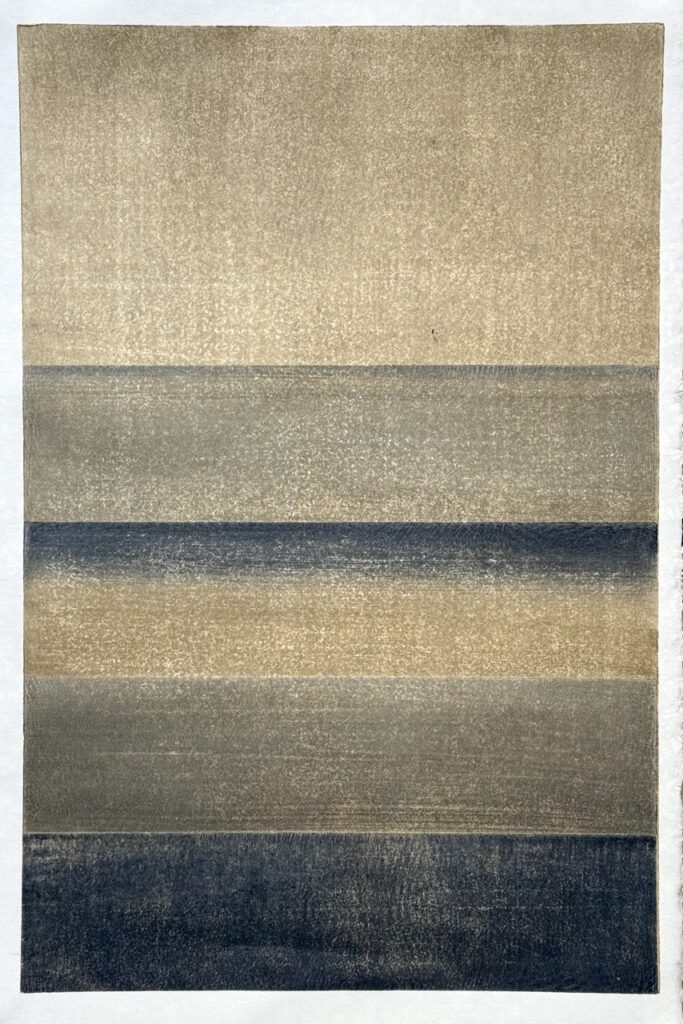

The experiment extends into a modular series, where multiple impressions, obtained from the stratification of different blocks, evoke the changing water levels and sedimentation. The work surpasses reduction printing to focus on the superposition of layers, representing and reflecting on the idea of what a map is and how it can be built “from within” the place. The series establishes a visual grammar of height, depth, and trace, consolidating an aesthetic of the threshold between land and water.

Maps of Water (Mappe d’Acqua) is therefore presented as a multi-dimensional project: a critical reflection on cartography as a tool of power and on the inequality of the view from above, but also an intimate exploration of changing matter. The work aspires to transcend the mere image, seeking to convey the survival of water, its trace, and its weight. As Greer states, visual research, when applied to complex problems, can contribute to wider discourse, both in developing alternative methodologies for approaching the issues and in finding communication solutions. The goal is to allow the visual memories of distant landscapes to dialogue.